Friday News Roundup - September 8, 2023

Friday greetings from Washington, D.C. While the unofficial end to summer was Labor Day weekend, the summer heat wave continued this week. Senate leaders also turned up the heat on the House, as Senate Republicans moved to support additional defense spending, including for Ukraine, along with disaster aid. Significant differences still remain too on spending measures. The deadline of September 30th remains for a spending deal, or at least a continuing resolution, to keep government open, as well as the end of the year deadline to avoid the 1% across-the-board cuts imposed by the debt ceiling deal. For some in the House, the risk of a shutdown is overblown, and those 1% cuts are just the start of something bigger. Meanwhile, in the Senate, the spending bills are being debated under regular order.

Normally, the unveiling of a cell phone would not be major news in Washington, but the unveiling of the Huawei Mate 60 Pro and a Chinese processor that outstrips intended U.S. and allied export controls has prompted renewed discussion about China’s tech capabilities. At the same time Beijing announced that it would ban iPhone’s from the offices of government agencies and state-owned industries, taking $200 billion off of Apple’s market cap.

This week, the National Defense University’s PRISM Journal published Joshua C. Huminski’s–the Director of the Mike Rogers Center for Intelligence & Global Affairs–piece “Russia, Ukraine, and the Future Use of Strategic Intelligence” on how the United States used strategic intelligence to inform allied discussions and preparations for Russia’s expanded invasion of Ukraine, and how this campaign reflected past successes and failures.

In this week’s roundup, Dan Mahaffee looks at the importance of leadership as he looks at the geopolitical and economic stories we’ve tracked in the past month. Ethan Brown addresses the risk of hold ups in the AUKUS negotiations. Veera Parko covers what French President Macron is signaling regarding his foreign policy priorities, and Hidetoshi Azuma tracks the statements from Moscow aggravating historical frictions with Japan.

Leadership in a time of Geopolitical Uncertainty

Dan Mahaffee

With August and the Labor Day holiday in the rear-view mirror, it was a good time to take stock of what is going on at home and around the globe. That we live in a time of geopolitical and economic transition is clear. Realignments in the economy, politics, and the overall impact of technology unfold over years, if not decades, even if we read them in short paragraphs in the history books. In these challenges, it is important that we use all the tools of national power to address this contest, but how can the American people and our allies be encouraged to continue to rise to the challenge? Pulling together several threads tracked since July, the story of this geopolitical shift and the importance of leadership become clear.

The most recent headlines from this week tell us of the geopolitical and economic shifts and splits taking place. The upcoming G20 summit in Delhi and the pomp displayed by the Modi administration in hosting the event demonstrate India’s (or Bahrat’s) leadership on the global stage. As Xi and Putin stay home — with Xi previously opting to attend the BRICS summit in South Africa. In emphasizing the importance of the BRICS, Xi demonstrates how he sees the group as a counterweight to the G7, while the irony is not lost on me of an anti-western bloc originally named after a Goldman Sachs analysis. Still, what does this mean for the future of the G20? In The Washington Post, Ishaan Tharoor has an expert summary of how Delhi’s leadership of the G20 comes while India is also hedging between Washington, Beijing, and Moscow and seeking to lead the global south.

With China and Russia sending understudies to the summit, the Biden administration hopes that the summit is an opportunity to demonstrate U.S. engagement and leadership on issues affecting the nations of the Global South. While Ukraine and Taiwan are on the top of the agenda for U.S. geopolitical concerns, as Tharoor notes, the concerns of many other countries are focused on trade, economic growth, and dealing with inflation and rising borrowing costs. Combine this with the overall pressure of the climate crisis and pressures of the energy transition, competition, not cooperation appears more likely between the great powers. Non-aligned nations will seek to play Washington, Brussels, Tokyo, etc. off of Beijing, Moscow, Tehran, etc.

The headlines demonstrate that this is not only a geopolitical division, but also a division in economic systems and technology platforms. The unveiling this week of the Huawei Mate 60 Pro smartphone with a 7nm processing chip illustrates how China has moved to develop semiconductors beyond the limits put in place by earlier U.S. export controls. At the same time, authorities in Beijing announced that the Apple iPhone would be forbidden in the workplaces of central and local government officials and employees of state-owned industries. China has demonstrated that it can close the semiconductor gap, but it remains to be seen whether it can produce them at scale. U.S. and allied authorities will want to learn more about the chip and how it was produced. There will be pressure to expand export controls, and more of the economic and trade tit-for-tat could ensue, but ultimately we are moving towards two technological systems. We will have to demonstrate in these advanced technologies, as well as the green energy transition, that our system is the superior one compared to the way China will wield technology.

Critical to the success of both a technology-driven economy and the development of a carbon-free economy will be access to secure supply chains and the resources that are the building blocks of modern chips, batteries, motors, etc., as well as the fuels for nuclear and alternative energies. To this end, tracking the coups across West Africa has demonstrated how at a time of weakened western engagement with the region, Russia was able to easily upset the balance of power in the region. In many ways, engagement from the United States and European allies in the regions remained focused on counterterror operations — critical to near-term stability, but no longer a strategic priority. Old colonial or Cold War paradigms of simply forcing our way into the region’s for a solution — and access to resources — will not provide a stable solution. Our support would do best to demonstrate how the U.S. and their allies can provide the Global South with viable and beneficial alternatives to what China and Russia offer, not always surging attention after Beijing and Moscow have already established their foothold.

Zooming in on the details of the coup in Niger, it was clear that our engagement had flagged, and the diplomatic vacancies — no U.S. ambassador in Niger, neighboring Nigeria, or to the African Union at the time of the coup — resulting from both slow personnel processes and political blocks on Senate nominations. This is one example of how our petty partisan politics endanger the functioning of foreign policy and national security. While the vitality of our leaders is important imagery for leadership on the global stage — and the age of leaders on both sides of the aisle is a real concern — so too is the practical functioning of our government and its ability to deliver results. Ironically, where President Biden has delivered — keeping Ukraine allies together, bridging the historic divide between Japan and Korea, and building the infrastructure to underpin U.S. technology and green energy leadership — these are all areas where voters either ignore foreign policy or the economic benefits will take time to develop. Still it is important to demonstrate the benefits of U.S. global leadership for both our allies and the American people.

The importance of demonstrating the benefits to the American people are even more critical following the sentiments displayed at the GOP presidential primary debate, as well as the America First approach that the former president continues to take. When I mentioned that the rest of the world has more important priorities than Ukraine’s offensive and Taiwan’s security, many Americans also share that same sentiment. Perhaps what is lost in the discussion of the various technologies, foreign summits, and far-off coups is the more fundamental nature of the contest we face. Even if underwhelmed with the options on the stage of this political debate or future ones, we have the option of choosing and changing our leaders. The forces that we are against — and what we see the people of Ukraine fighting against now — seek to keep that choice from their people and take it from others. Democracies will have to demonstrate that they can deliver not just better products and better results, but also better leadership.

The risks of AUKUS hold-ups

Ethan Brown

The USS Texas fast-attack submarine visits Yokosuka

AUKUS, the ground-breaking deal secured two years ago that would increase maritime and technology security between Australia, the UK, and the United States, continues to face challenges in its most fundamental components: technology exchanges. This is the issue underlying congressional leaders from the United States and key parliamentary actors from the UK this week, the former who were aiming at increasing anti-China security policy, while the latter stuck to the elephant in the room: transfer of technology between long-standing partners.

The hold up on technology transfers stems from restrictions in US export of defense and security technology. These restrictions are established by the International Traffic and Arms Regulations, known as ITAR, codified under Title 22 of the U.S. Code, or to be more obfuscated, Title 22 (Foreign Affairs), Chapter I (Department of State), Subchapter M (ITAR), Part 122 (registration of manufacturers) and Part 123 (Licenses for the Export and Temporary Import of Defense Articles). Therein, the limitations of exchange of technological data are such that jointly-developed technologies, in the case of Pillars One and Two of AUKUS, nuclear submarine technology and additional weapons technologies (hypersonics, satellite and natsec space, and electronics) would still be subject to the stringent limitations placed on US defense tech export. While Australia and the UK have myriad exemptions for transfer of existing technology (under subsection 123.15 subject to Section 36(c) of the Arms Export Control Act), that collaborative development — which really underpins the entirety of the AUKUS deal — is the main hurdle.

It’s a matter of congress and the department of state at odds over the limitations of ITAR, and concerns of technologies ending up in the wrong hands… in this case, China. That transfer of technology that is of such concern are the Virginia-class submarines that bolster the maritime performance and security that underwrites the Australia-contribution to the deal. There is no clear or stated exemption on the transfer of these nuclear titans to partners of any ilk. And these particular weapons systems are, undoubtedly, the biggest and baddest of the underwater world, making their sharing of technology a sticking point in the laborious constraints in the ITAR regulations.

But for Australia and the UK to be shorted by these obscure and minute constraints is baffling, and the inability of congress to advance legislation that exempts State Department adherence to the ITAR protocols is a baffling one. First, Australia and the UK are, beyond a doubt, some of, if not America’s closest allies within the rules-based order. Both nations are plank-holder members of the Five-Eyes intelligence and security partnership, (Canada and New Zealand rounding out the Five). For proof positive, the UK and Canberra stood side-by-side with the United States during the long years of the War on Terror from its earliest moments, and have built the bulwark of military and security cooperation in both the European and Pacific theaters for generations.Although it should be noted that Australia’s entry into the multi-modal trade of defense tech was formally established in 2012 and 2013 under the Defense Trade Cooperation Treaties subject to consultation with the DoD by the State Department under Title 22 of the Foreign Military Sales code. All components of these exchanges are regulated by the Arms Export Control Act (AECA), which is dominated by the State Department under existing legislation.

If the nature of intelligence sharing because allies at the highest levels is not enough to be a deterrent for the exchange between the United States, Australia, and the UK, then it should serve as a precedent for the AUKUS technology exchange. It’s simply a common-sense analogy that seems to be missing from the discussion on regulatory restrictions… letter of the law getting in the way of what makes sense for the now and future. Republicans in congress are among those who are most keen to pursue the AUKUS exemptions, and the battle — whether it be partisan or other unclear motivations — seems to be between the GOP who want to rescind or eliminate those restrictions, and the Democrat bodies and Biden’s State Departments who aren’t yet following suit. President Biden, for his part, has never once wavered on the criticality of increased Indo-Pacific cooperation, so this mess appears to be a battle being fought in the widgets of the congressional labyrinth.

What are the problems with AUKUS tech-swapping being held up? For one thing, interoperability between partners at a strategic scale. Another precedent (one which proves the critical necessity for this type of interoperability) is the vaunted F-35 Joint Strike Fighter Program (another existing template of exchange between the US, UK, and Australia, to include many others). The F-35 operates on the Multifunction Advance Data Link (MADL) network, a electronic marvel that ensures all 700~ F-35s in production — released only to those allies deemed trustworthy with this kind of revolutionary tech — are continuously updating targeting and mission data. So if one F-35 from Hill AFB in Utah takes off, and begins data-streaming, every other F-35 on the planet is receiving and sharing operational data via the MADL. Of course, the US still retains some highly classified features, capabilities, and mission information on this exclusive platform, just like any rational nation would with next-gen tech. But by and large, the F-35 revolution fused air power and sensor capabilities between the United States and its allies like never before.

Australia aims to design and produce its own nuclear submarine fleet to bolster Indo-Pacific security, but these won’t be available until 2040 at the earliest. And hitting that mark will require the collaborative efforts with the US and UK which are held up by ITAR and AECA red tape.

AUKUS and the submarine technology exchange, along with the hypersonics, the satellites, electronic warfare, and all the other components of the deals Pillars, would serve essentially the exact same function. But this would be developmental technology exclusive to the tried of AUKUS signatories, it’s not being exported to second- and third-tier security partners. Among our myriad allies and security cooperators, limiting the exchange and development of advanced security capabilities, when a strategic deal is already established in policy, is not reasonable, and the reasons for constraining the advancement of this deal are even less rational.

How does congress get past this? Title 10 of the US Code §8677 stipulates that any transfer of naval vessels exceeding 3000 tonnes or is less than two decades in operational age requires “specific authorization by law.” So it becomes a question of whether both chambers of the congress can come to terms on advancing a critical capability. It should be a clear bipartisan issue but…red tape and interminable constraints rears its ugly head. It’s not unprecedented for US technology being shared to remain under remit of US decision-making, a la the F-35 in many cases, but moving forward in any capacity requires that the American congress resolves to do something definitive so that the various vectors of Australia’s defense capabilities can start this generational-endeavor of maritime security. Otherwise, AUKUS becomes a largely toothless spectacle after serving as a shot across the bow for China’s Pacific ambitions.

Macron’s foreign policy priorities and EU enlargement

Veera Parko

On Monday August 28, French President Emmanuel Macron made a foreign policy speech at an annual meeting of French ambassadors in Paris. His remarks on European Union reform and potential enlargement from the current 29 Member States to Ukraine and Moldova reflect the current discussion in Brussels on how the EU needs to evolve to respond to future challenges. The message the EU will send to potential new member states is important, especially with regard to the ongoing war in Ukraine. This week, French Europe minister Laurence Boone advocated a clear signal for candidate countries towards gaining full membership in order to protect them from Russian disinformation campaigns — in Moldova, this has been particularly pronounced.

The debate on EU enlargement and further integration is by no means new. Throughout its existence, the EU has been struggling to find a balance between deeper political integration (some might call this federalism) and more flexible decision-making by small groups of countries. In his speech, President Macron said the EU will face problems if enlargement into Ukraine and the Western Balkans is not combined with reforms in the bloc’s decision-making process. According to Macron, a “multi-speed” Europe on enlargement should be considered: in practice, this would potentially mean that some EU candidate countries could go forward with more integrated policies and be granted some benefits of membership before full accession. The President said France would come back to concrete suggestions on how to do this at a later stage.

In his speech, Macron also provided other insights on Europe’s foreign and security policy. According to Macron, Europe and the West in general faces a risk of getting weaker on the world stage in terms of its economic power, energy production capacity and aging population. He continued to state that in recent years, the current international order has been challenged by actors seeking to build an alternative world order — as an example, he mentioned the expansion of BRICS. President Macron also laid out four priorities for French foreign and security policy: security and stability, European independence, France as a global “trusted partner”, and outreach and influence.

Macron’s remarks on the implications on the war in Ukraine for European security architecture are of particular interest. In traditional French fashion, he called for a stronger “European pillar” and stronger European defense within NATO and European strategic autonomy, adding that taking more responsibility for its own defense will make European NATO nations more, not less, reliable partners for the United States. On China and the Indo-Pacific, he stated that China remains an important partner on issues such as climate, and France will continue to engage with China in a “non-naïve” and pragmatic fashion.

The EU’s potential enlargement to Ukraine and Moldova would certainly have an impact on the balance of power inside the EU, and how the Union will formulate its foreign policy positions in the future; colleague Ethan Brown and I wrote a piece on this for the Diplomatic Courier recently. At this point, one can only speculate what Ukraine and other candidate countries’ accession would mean in practice — a more unified Europe on Russia and China, a stronger European defense and transatlantic partnership, or groups of like-minded European countries going forward on climate action, foreign policy or energy? In the past, France has been skeptical of enlarging the Union and thus undermining the bloc’s decision-making capacity. Whether combining a new pro-enlargement position with the old idea of a multi-speed Europe will provide a solution that will be in France’s interest, time will tell.

Russia’s Renewed History Offensive against Japan

Hidetoshi Azuma

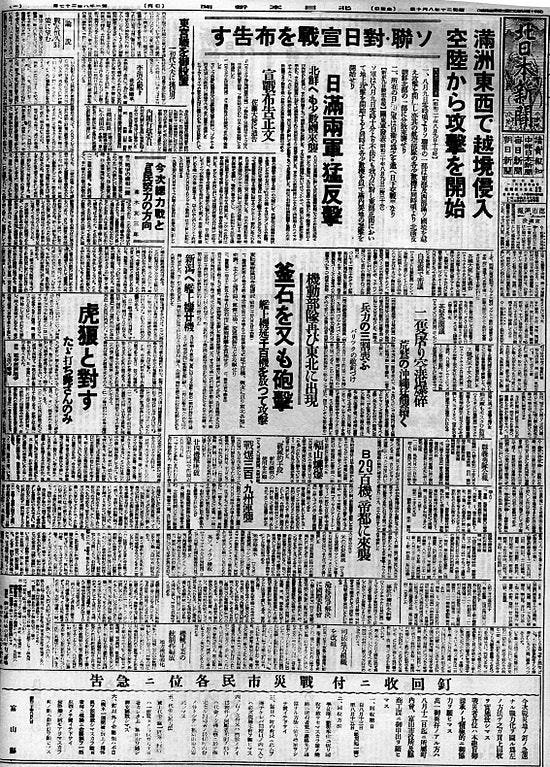

The Japanese newspaper, Kita Nippon Shimbun, reports on the Soviet Union’s entry into the Pacific theater of WWII on August 9, 1945 (Photo Credit: Wikimedia Commons)

The former Russian President Dmitry Medvedev issued a stern warning against the alleged revival of Japanese militarism on the Far Eastern island of Sakhalin on September 3 in commemoration of the end of WWII. Medevedev’s latest diatribe against Japan was nothing new and even unsurprising given his track record. Indeed, he had previously called on the Japanese Prime Minister Fumio Kishida to “commit seppuku” to expiate the humiliation of Japan’s supposed subordination to the United States earlier this year. In addition to being the Kremlin’s veritable troll-in-chief these days, Medvedev has also been the Russian President Vladimir Putin’s geopolitical point man for the Far East since the late 2000s, routinely provoking Japan to advance Moscow’s regional interests. In particular, Japan’s imperial past has increasingly provided Moscow with useful fodder for weaponizing history as part of its regional strategy. Medvedev’s latest stunt in the Far East occurred against the backdrop of Moscow’s renewed history offensive against Japan driven by the Kremlin’s official designation of September 3 as “the Day of Victory over Militaristic Japan and the end of World War II ‘’ back in June. It marked a consequential shift in Moscow’s regional strategy as it symbolized the emerging de facto Sino-Russian alliance threatening Japan from its both northern and southern flanks.

Historically, Moscow’s weaponization of Japan’s imperial past aimed to undermine the US-Japan alliance. This was due to Russia’s limited geopolitical influence in the Far East in which it struggled to overcome the American regional power after WWII. After all, Russia’s defeat of Imperial Japan was thanks almost entirely to the US, which had virtually annihilated Japan’s any remaining military power and even implemented the controversial Operation Hula to train the Red Army’s amphibious warfare capabilities in preparation for the Soviet entry into the Pacific theater in August 1945. Indeed, while the US dominated the entire Japanese archipelago after 1945, Russia barely succeeded in closing off the Sea of Okhotsk by occupying its littorals, including the Sakhalin island and the Kuril island chain. In other words, the Soviet victory in 1945 did not translate into the country’s ascendancy as a regional power, let alone a maritime power, in the Asia-Pacific with its warm water ports facing the Pacific Ocean effectively limited to those near the forlorn Avacha Bay on the Kamchatka Peninsula. As a result, Moscow has relied heavily on influence operations to undermine the US-Japan alliance in hopes of offsetting Russia’s geostrategic disadvantages in the Far East. Japan’s contested history provided more than plenty of fodder for Moscow’s regional strategy.

Therefore, the focus of Moscow’s history offensive has traditionally revolved around historical memories related to the US. The US dropping of atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki has invariably ranked among the Kremlin’s favorite topics for its disinformation directed against the US-Japan alliance. Indeed, the attendance in the annual Hiroshima Peace Memorial Ceremony by the Russian ambassador to Japan has become a thing of a ritual in Moscow’s indefatigable efforts to discredit the US in Japan. The controversial history of the so-called Unit 731 biological warfare unit in Manchukuo has also become an important topic for Moscow’s history offensive against Japan especially since the 2010s. Although Unit 731 undoubtedly existed with its own heinous track record, the prevailing narrative purporting to portray the grisly spectacle of human experiments remains contestable at best and was likely a product of Moscow’s disinformation efforts under the Soviet leader Yuri Andropov in the early 1980s. What is indisputable, however, is that the US struck a deal with former Unit 731 members by trading impunity for intelligence on biological warfare after WWII as documented well by the declassified US papers. This fact alone has driven Moscow’s growing weaponization of Unit 731’s contentious history in recent years due to its perceived advantage of simultaneously disrupting the US-Japan alliance and courting China toward a geopolitical unity in Asia.

Russia’s expanded invasion of Ukraine beginning in February 2022 has fundamentally changed the character of Moscow’s history offensive against Japan. While its traditional focus on Hiroshima/Nagasaki and Unit 731 has endured, Russia’s growing decoupling from the US-led rules-based international order has driven Moscow to propagate an alternative narrative of WWII with a peculiar emphasis on the Soviet role in defeating Imperial Japan. According to this narrative, it was the Soviet entry into the Pacific theater, not the US dropping of atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, which delivered the coup de grace to Imperial Japan and brought about an end to WWII. Moreover, the US dominance of post-WWII Japan essentially froze the supposed denazification process of the defeated empire due to Washington’s protection of Unit 731 members and sponsorship of the anti-communist Liberal Democratic Party (LDP). In other words, the US preserved the Nazi remnants in post-WWII Japan just as it supposedly did in Ukraine after 1945, the narrative justifying Moscow’s ongoing war in Ukraine. The upshot of Moscow’s latest history offensive against Japan has manifested itself in the form of the Kremlin’s recent passage of the June 2022 bill calling for the recognition of “the Day of Victory over Militaristic Japan and the end of World War II ‘’ on September 3 instead of September 2 on which Imperial Japan signed the Instrument of Surrender aboard the USS Missouri in 1945.

In this sense, Medvedev’s appearance in Sakhalin earlier this week heralded a new era of the Japan-Russia relations. Moscow’s recognition of September 3 as marking the end of WWII essentially signified the resurrection of the Soviet leader Joseph Stalin’s policy which was abandoned after the Cold War in favor of September 2. As China also recognizes September 3 as the date WWII ended and celebrates its own Victory Day over Japan, Moscow’s latest reinterpretation of history was more than just Stalinist retrogression and provided a new meaning to the budding Sino-Russian relations. Indeed, the Chinese President Xi Jinping’s historic summit with Putin in Beijing this past March underscored the emergence of a de facto alliance between the world’s two leading authoritarian powers. Given Beijing’s covert support to Moscow’s war in Ukraine, a possible Chinese invasion of Taiwan would almost inevitably entail some sort of Russian involvement. This prospect would be especially salient for Japan as Tokyo increasingly views itself inevitably involved in what it calls “a Taiwan contingency.

In other words, while Japan must show its “will to fight” as recently called for by the former Japanese prime minister Taro Aso in Taiwan in August, it must be ready for a potential two-front war simultaneously encroaching upon the country’s northern and southern flanks. While Russia’s amphibious warfare capabilities may remain limited in the Far East, the country has a wide range of options capable of causing nuisance as Japan seeks to focus on its southern flank. Indeed, Russia remains a preeminent cyber power and could easily wreak havoc on Japan’s fragile cyber defense system which Tokyo has consistently failed to improve despite Washington’s persistent demands over the years. Moreover, Moscow’s extensive use of the private military company, the Wagner Group, across the world could portend a possible Wagner invasion of Hokkaido, Japan’s northernmost island located less than 4 km off the coast of the Russia-controlled southern Kuril Islands and 37 km from the Sakhalin Island.

However unlikely such a scenario may be, the impossible often happens in Russia. Indeed, few foresaw the Wagner uprising against the Kremlin this past June when Putin initiated Russia’s expanded invasion of Ukraine in February 2022. Harking back to the 19th-century Russian statesman, one is starkly reminded of the perennial wisdom that Russia cannot be understood with mind and can only be believed in. Yet, history also shows that the very act of putting faith in Russia has almost invariably proven suicidal. Tokyo’s current Russia policy continues to rest on the dubious faith that Moscow would somehow remain detached from the so-called Taiwan contingency, especially given its rancorous internal strife at home and on the front. However, the Kremlin’s renewed history offensive emboldened by the burgeoning Sino-Russian relations appears to contradict such faith and could indeed precede the impossible poised to overtake Japan’s uncertain fate.

News you may have missed will resume in late September.

The views of authors are their own and not that of CSPC.