Transportation In the Revolutionary period

In 1776,

the recently declared “United States of America” relied largely on waterways for transportation. Roads were limited in scale and often in rough condition. Very few population centers were dense enough for extensive road networks.

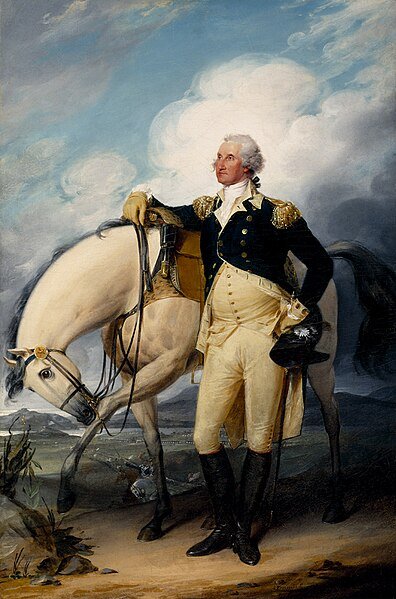

“The Flying Machine,” pictured here, was one exception that commercialized wagon transport over short distances (Federal Highway Administration, CC BY 2.0). Read on to learn more about how Americans traveled in 1776.

“Good roads, canals, and navigable rivers, by diminishing the expense of carriage, put the remote parts of the country more nearly upon a level with those in the neighbourhood of the town. They are upon that account the greatest of all improvements. They encourage the cultivation of the remote, which must always be the most extensive circle of the country. They are advantageous to the town, by breaking down the monopoly of the country in its neighbourhood.”

Traveling by land

In the late 18th century, walking was the most common and cheapest mode of transportation, used for distances to get supplies or visit others. Roads were generally deteriorated and unpaved, which made traveling by land dangerous. However, for those who could afford it, wagons and horses enabled traveling for business or across longer distances. The “Flying Machine” (pictured above) was an express route that took passengers from New York to Philadelphia in two days.

Who could travel?

Given that long-distance travel was typically reserved for business, men generally traveled far more than women. Of these men, most were merchants, planters, post riders and government officials. Enslaved African-Americans required permission or accompaniment to travel, otherwise they would be considered runaways.

Turnpikes and Toll Roads

The infrastructure of toll roads, or “turnpikes”, began to emerge as a critical solution to the deteriorating state of public roads following the American Revolution. These turnpikes, initially named for the barrier (or "pike") that would block the road until the toll was paid, played a crucial role in enhancing transportation infrastructure by providing better-maintained, stone-surfaced roads that facilitated commerce and movement across the growing nation.

The Trésaguet Technique

Toll roads were constructed by contractors or laborers supervised by trained road builders, a shift from the older practice of using inefficient statute labor. These roads were well-engineered, often following the standards of French road director Pierre-Marie-Jérôme Trésaguet.

While roads such as the Great Conestoga Road had been funded by individual colonies, the Seven Years’ War and the Revolutionary War would leave the newly founded state legislatures with minimal resources and political growing pains would set back infrastructure projects. Such was the case in Lancaster, Pennsylvania where residents had been petitioning for a main road since 1730. In 1792 a bill was finally passed and, like many other states, they hired a private company while still relying on tolls to fund the project. Prior to 1776, tolls were far less common.

The completed road was labeled the Philadelphia and Lancaster Turnpike, and was the first major turnpike in the new nation. A horse and rider could travel 10 miles for 6 cents (around $1.91 today) along the 64-mile road. According to the U.S. Department of Transportation:

“[The Lancaster Turnpike was] the first long-distance broken-stone and gravel surface built in America according to formal plans and specifications. The road's construction marked the beginning of organized road improvement after the long period of economic confusion following the American Revolution.”

Traveling by water

Water transport allowed people to travel inland far quicker than by road. Waterways in cities also allowed for transport across the ocean. The abundance of natural resources made American ports effective shipbuilding yards. As such by 1776, the colonies were leading producers of British vessels; with 30% of British merchant vessels made in the New World by 1750. Following the signing of the Declaration of Independence, the nation no longer had the protection of the Royal Navy for trade. Nonetheless, sea vessels would make the treacherous 6 to 8 week journey as the only way to cross the Atlantic.

Who could travel?

Inland waterway travel was most commonly utilized for trade and to reach major towns and cities. Of those who chose to make the journey across the sea were officials, traders, and new immigrants. In 1774, the Continental Congress banned the import of enslaved Africans as part of an effort to boycott all British imports. However, enforcing the ban was difficult and Southern states still continued the demand of the Transatlantic Slave Trade. The risks of death and diseases for enslaved Africans were far greater than for European travelers due to inhumane treatment on ships.

Who built the ships?

The New England colonies were the top producers of sea vessels, and many of the vessels commissioned by the Continental Congress in 1775 were built in shipyards across New Hampshire, Massachusetts, and Pennsylvania. By 1776, there were 27 warships built for the new Continental Navy. However, this was a small number in comparison to the nearly 270 warships comprising the British Royal Navy. The American solution to this gap was privateers; merchant seamen who would obtain a contract to take over British vessels. To avoid losing their ships and risking their lives, privateers usually captured smaller Navy vessels and merchant ships.

Vessels used on inland waterways

Merchant Barges

Merchant barges could travel long distances for trade. The Lady Washington, shown here, was used in present-day Oregon for fur trade in the 1780s. She eventually reached Japan and the Philippines as well.

Batteau

As described by historian Joseph Meany Jr., “by the 18th century batteaux were the most common and most important cargo carrier found on the inland waters of colonial North America.”

Birchbark Canoes

These canoes were invented by Indigenous communities in the Great Lakes region but were used throughout the United States. Their narrow structure made them well-suited for travel across rivers.

Durham Boats

Used along the Delaware River to transport freight and on occasion George Washington’s men. Watch the video below to learn more about Durham Boats!

The rise of canals

Boats such as the ones above often preferred to travel and transport goods over land. Freight included furs, produce, textiles and more. As such, these vessels were responsible for securing the nation’s trade position globally which would be critical after the costs of the Revolution.

However, these boats would soon be replaced during the era of canals. The first canal was built in 1793 around Conewago Falls on the Susquehanna River near York Haven. While some of the previously mentioned vessels would initially be used in canals, canal boats would become the norm by the 1800s as they had a greater cargo capacity.

“The earliest movement toward developing the inland waterways of the country began (in 1787) when, under the influence of George Washington, Virginia and Maryland appointed commissioners primarily to consider the navigation and improvement of the Potomac; (...) a further conference was arranged in Philadelphia in 1787, with delegates from all the States. There the deliberations resulted in the framing of the Constitution, whereby the thirteen original States were united primarily on a commercial basis — the commerce of the times being chiefly by water.”

Module by Maria Reyes Pacheco, with contributions from Saakshi Philip. Click here for bibliography.