Friday News Roundup — August 2, 2024

Any hopes that the war in the Middle East that is destabilizing the global order and threatening to once again draw the United States directly into the fighting would finally relent in response to the Biden administration’s intense ceasefire efforts were dashed this week. The Middle East has a way of doing that.

Earlier this week Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu cut short a controversial trip to the United States in the midst of a heated presidential campaign. In Washington, D.C., he gave a defiant speech to Congress promising that Israel will totally vanquish its foes in its ongoing war against Iranian proxies Hamas, Hezbollah, and the Houthis of Yemen. Netanyahu returned home early after a missile attack on the Golan Heights reportedly killed a dozen people, most of them children playing on a soccer field.

Israel’s forceful response came quickly.

On Tuesday, Israeli forces launched an airstrike on Beirut, Lebanon that killed Faud Shukr, a senior commander of the Lebanese Hezbollah terrorist group, which Jerusalem blames for the attack on the Golan Heights. The next day a presumed Israeli strike assassinated Hamas political leader Ismail Haniyeh in the heart of Tehran, where he was visiting Iran’s capital to attend the inauguration of the newly elected president. As Hamas’ political director, Haniyeh was central to U.S.-led negotiations for a ceasefire in Gaza and a return of Israeli hostages held by the terrorist group. That deal now lies in tatters.

Iranian, Hezbollah, and Hamas leaders have all pledged revenge for the Israeli assassinations, and many observers fear the rapidly escalating tit-for-tat violence may soon engulf the region in all-out war. The Pentagon is certainly taking that threat seriously, reportedly surging additional combat aircraft to the region in response. That deployment recalls operations last April, when U.S. fighter aircraft based in the region, joined by their counterparts from Jordan, France, Saudi Arabia, and Britain, shot down many of the 300 drones and missiles that Tehran launched against Israel.

Elsewhere in world affairs, thousands of people demonstrated across Venezuela this week to protest what many election observers characterized as a stolen election that named the dictator Nicolas Maduro as president for another six-year term, despite strong evidence and polling data indicating that opposition candidate Edmundo González won in a landslide. On Thursday, Secretary of State Antony Blinkin announced that the United States had recognized Gonzalez as the true winner, increasing the pressure on the Venezuelan strongman to step down.

Since taking the reins of power from his mentor and strongman model Hugo Chavez, Maduro has overseen Venezuela’s descent into a failed state, with more than 7.7 million Venezuelans — or roughly 20 percent of the population — fleeing the country since 2014. That amounts to the largest exodus in Latin America in modern history.

In a welcome bit of good news, after many months of painstaking negotiations, the Biden administration announced yesterday that it had secured the release of three American citizens held by Russia — Wall Street Journal reporter Evan Gershkovich, Marine veteran Paul Whelan, and Russian-American radio journalist Alsu Kurmasheva. They were part of a complex 24-person prisoner swap involving Russia, the United States, Germany, and three other Western allies. It amounted to the largest prisoner exchange of its kind since the end of the Cold War.

In return for releasing Western hostages, Russia received eight of its nationals being held in detention in Western countries, all of them having known or suspected ties to Russian intelligence. The released Russians included Vadim Krasikov, a convicted murderer who was sentenced to life in prison by a German court for assassinating a Russian dissident in Berlin.

In an emotional reunion, the three Americans were met by family members, President Joe Biden and Vice President Kamala Harris on the tarmac at Joint Base Andrews outside of Washington late last night. President Biden hailed the prisoner exchange as the result of patient, behind-the-scenes diplomacy and alliance nurturing. “Everybody thinks I talk about the notion of relationships and foreign policy with other countries,” he said. But “it matters if other leaders trust you, you trust them, and you get things done.”

James Kitfield is a CSPC Senior Fellow

U.S. Unprepared for Global Threats

By Ethan Brown

The Commission on the National Defense Strategy has concluded its most recent cycle, rendering judgment on the 2022 NDS, and the summary of the report issued Congress a stark warning: “The United States last fought a global conflict during World War II, which ended nearly 80 years ago. The Nation was last prepared for such a fight during the Cold War, which ended 35 years ago. It is not prepared today.”

Over the past roughly five to seven years, grand strategists have sought to pull the Western, counterterror-focused warfighting capabilities out of Afghanistan and Iraq and pivot resourcing towards this broad, vague thing we call strategic competition. That latter construct is incredibly broad and all-encompassing, to include incorporation of gray zone operations (the likes of which have been quite effective by Russia as pre-war shaping measures, as well as China, and Iran, and others seeking to destabilize short of open-conflict), economic warfare, disinformation operations, and cyber engagement so as to force the liberal order to face threats on all fronts. Overwhelming/overstimulating the opponent through subversive, less-than-open- and alternative forms of conflict is a viable strategy when facing an overpowered adversary, and it’s one which Western adversaries do not necessarily need to cooperate on, these methods can be applied unilaterally to multilateral effect.

The Commission report focuses largely on three key shortcomings for the U.S. national security preparedness and resourcing:

The ineffectual and risk-averse business practices for DoD research and development and integration of new technologies facilitated by a flagging U.S. defense industrial base which is sorely lacking in production capacity

A US military lacking in capabilities and capacity required to be confident in deterrence and confident in its ability to prevail in combat

An uninformed (disinterested) U.S. public is “unaware of the United States faces or the costs (financial and otherwise) required to adequately prepare.

Further, the report takes issue with the vagueness of the 2022 NDS’ “integrated deterrence” model, which prompts collaborative and burden-sharing between the U.S. and ally/partner states in regions affected by instability, without providing substance or vectors to achieve the same. The review goes deeper to acknowledge that adversaries (the usual suspects) have managed to align military, economic, diplomatic, financial and industrial components, “all elements of national power,” and that the United States must necessarily do the same.

Of the issues cited in the study, of concern is the emphasis on technology and industrial production over management of human hardware, an issue I’ve opined for years regarding the DoD’s tech obsession (which necessarily infers my obsession over the ongoing recruiting crisis). But most concerning, perhaps, is the widespread uninformed and disinterested American public in the face of the international fragility and the inherent burden born by the United States. Call it the privilege of being a developed nation (and indisputably the most prosperous and free), but the mandate that citizens of a democracy be prepared to bear up the burdens of liberalism in a chaotic world are a harsh reality, and as Americans, we may have forgotten that truth which our grandparents understood 80~ years ago (circa World War II).

It’s difficult to imagine how our society will react to the 8AM news bulletin when Taiwan ends up under blockade, sending shockwaves throughout global commerce, or when a greater conflagration breaks out across the Levant (Middle East) and Africa, where a suddenly undermanned American military is going to have to begin committing men and materiel. But we can project, looking back to February 2022 when, on the 24th, war broke out on the European continent between Ukraine and Russia, and even though this outcome had been predicted for months, it still shook American society and our global economy has yet to recover.

“Even short of all-out war, the global economic damage from a Chinese blockade of Taiwan has been estimated to cost $5 trillion, or 5 percent of global gross domestic product (GDP). War with a major power would affect the life of every American in ways we can only begin to imagine. Deterring war by projecting strength and ensuring economic and domestic resilience is far preferable to and less costly than war.”

As a society, we are most certainly not prepared for war… real, total, nation-engrossing war. The twenty years spent in the Global War on Terror and its subsequent rebranding to the post-9/11 wars were not the sort of thing that required average Americans to commit to a so-called war effort. And the whole-of-nation costs incurred when a society faces threat and risk of major defeat are going to be stark: supply chain disruptions which impact literally every aspect of our commerce and trade will be contracted. Energy supplies and data exchange will be disrupted. Amenities great and small which we take for granted will become scarce and expensive. And we as a society are not prepared to face that reality.

The report suggests that the cost of deterrence–currently going unpaid and using the Reagan-era 5–6% of GDP on defense spending as a standard–are the means to offset that potential societal crisis. The lack of technological capability on account of archaic and ineffective, inflexible defense industrial systems and the acquisitions process are cited are causal. New warfighting concepts are called for as a means to perform in an era of attributable systems, AI-enabled capabilities, hypersonics, electronic warfare, and cyber capabilities, as well as competition in information domains. More defense spending on big, complex, industry-driven systems, to summarize.

As much as this analyst hates being a contrarian (that’s a lie, I live for contrarianism), this is a faulty thesis by the commission and the report is focusing far too much on the big sticks and silver bullets, and less on the most critical resource: human hardware. It’s a trend with nearly every defense-related policy. The first seven chapters of the report focus on the industrial base, policy reform, spending (recommendation projects reflect a constant-spending uptick towards $1.3 trillion in the next few years), force organization, and doctrine adaptation. Chapter Eight finally mentions how to redress the recruiting crisis and acknowledges the shortfalls in personnel management by the DoD. Essentially, the personnel management crisis is an afterthought following recommendations to spend more on tech and systems. The inverse needs to be true, which impacts the whole-of-society need to prepare for conflict.

While it is certainly viable that the defense industrial base as an institution needs dramatic and comprehensive overhaul, and indeed requires significant legislative reform to seize much of the monopolization of the industry from the giants for innovative and venture capital entities to bring new capabilities to the fore, the best tech–silver bullets as I like to derisively call it–are largely pointless if the DoD and it’s attendant commercial, polity, and other partners are not maximizing the human hardware.

The commission report makes many viable points on the strategic shortfalls and general preparedness for conflict–though the pre-election timing of the report is suspicious and hardly non-partisan–it reflects a continued grand strategic failure to emphasize human hardware the personnel management, once again demonstrating that our strategic leaders place too much priority on money going to tools and tech over acquiring and preparing the men and women who are necessary to conduct the actual deterrence and potential fighting.

Ethan Brown is a CSPC Senior Fellow.

House Committee Targets China’s Trade Crimes

By Daphne Nwobike

Photo by Bernd 📷 Dittrich on Unsplash

On Thursday, July 25, members of The Select Committee on the Chinese Communist Party introduced the Protecting American Industry and Labor from International Trade Crimes Act. Spearheaded by Chairman John Moolenaar (R-MI), Congresswoman Ashley Hinson (R-IA), and Ranking Member Raja Krishnamoorthi (D-IL), this bi-partisan initiative seeks to reduce the ease with which foreign actors, particularly China, can carry out crimes violating US trade policy.

The well-being of the American economy is directly impacted by the strength of trade policies that prevent supply chain disruptions, boost global trade, and increase export-based revenue. However, with the strength of US trade laws comes even stronger attempts by foreign actors to evade the requirements and restrictions implemented to ensure fair play and honest trade. Import violations include ignoring tariffs, bypassing sanctions, and smuggling restricted goods, to name a few. These violations undermine the US economy and national security while amplifying tensions between the US and foreign counterparts, especially China.

Despite being an important source of trade for the US, China has continued to engage in behaviors that severely harm the US market. The United States Trade Representative (USTR) has asserted that China engages in “forced technology transfer, cyber-enabled theft of U.S. IP and trade secrets, discriminatory and nonmarket licensing practices, and state-funded strategic acquisitions of U.S. assets.” The Select Committee on the CCP also emphasizes that China engages in fraud, duty evasion, and transshipment practices that greatly benefit their economy but leave the US economy and consumers in shambles due to decreased manufacturing jobs, revenue loss, price distortion, and other adverse consequences.

In an attempt to curtail China’s rising lack of regard for US trade policy, the Biden administration urged the USTR to “increase tariffs under Section 301 of the Trade Act of 1974 on $18 billion of imports from China to protect American workers and businesses.” These tariffs would apply to sectors including steel and aluminum, semiconductors, electric vehicles (EVs), batteries, battery components and parts, critical minerals, solar cells, ship-to-shore cranes, and medical products. Despite these efforts from the Biden administration, China continues to dodge US restrictions. Just last month, Chinese executives met with Malaysian officials to obtain approval to “relocate their battery, medical devices, and semiconductor manufacturing” to Malaysia in hopes of avoiding US tariffs.

As trade tensions between the US and China intensify, government officials are seeking solutions to this persistent problem, hence the Select Committee on the CCP’s introduction of the Protecting American Industry and Labor from International Trade Crimes Act. According to the Select Committee, this legislation will implement stricter prosecution measures against international trade crimes such as duty evasion and trade fraud. Specifically, this Act will establish a new task force within the DOJ’s Criminal Division to investigate and prosecute trade-related crimes; enhance nationwide responses to trade-related offenses by providing training and technical assistance to other federal, state, and local law enforcement agencies; require the Attorney General to submit an annual report to Congress assessing the DOJ’s efforts, statistics on trade-related crimes, and fund utilization; and authorize $20,000,000 for FY 2025 to support these efforts with appropriate guardrails.

In a statement about this newly introduced bill, Ranking Member Raja Krishnamoorthi underscored its importance, stating, “For years, the Chinese Communist Party’s predatory trade policies have violated American trade laws and victimized American companies, workers, and consumers through trade crimes like dumping, duty evasion, and fraud…Whether it is dumping below-market iron and steel, flooding the American market with illegal vapes, or violating the Uyghur Forced Labor Prevention Act, we must send an unmistakable message to companies based in the People’s Republic of China that their illegal trade practices must end now.”

Daphne Nwobike is a CSPC Intern.

History Rhymes: Vindicating MacArthur’s Vision for Japan

By Hidetoshi Azuma

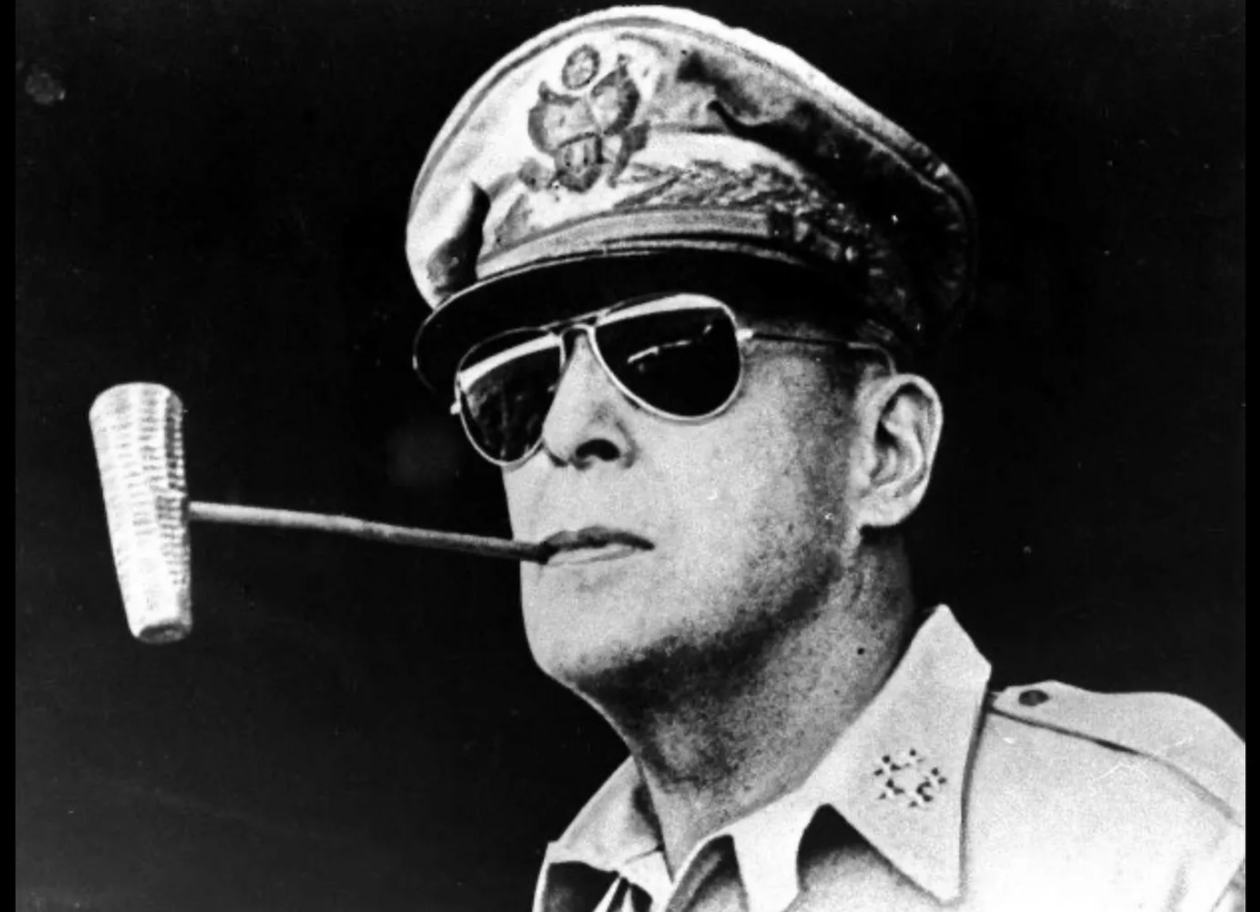

The General of the Army Douglas MacArthur sports his famous corn pipe aboard USS Missouri ahead of the signing of the Instrument of Surrender for Imperial Japan on September 2, 1945 (Photo Credit: Wikimedia Commons)

As the start of the 2024 Paris Olympics dominated the news cycle last week, a sea change in geopolitics quietly occurred in Japan. On July 28, the United States and Japan unveiled Washington’s plan to launch a joint command for the US Forces in Japan (USFJ) in Tokyo during the latest bilateral 2+2 foreign and defense ministerial summit. The USFJ currently lacks a local command in Japan and receives cues from the US Indo-Pacific Command (INDOPACOM) in Hawaii. The relocation of the USFJ command from Honolulu to Tokyo will fundamentally change the role of America’s forward military presence in Japan and its relationship with the Japanese Self-Defense Forces (JSDF). In fact, the emerging USFJ command in Tokyo evokes memories of General Douglas MacArthur during and after WWII, leaving an indeclinable mark on the evolution of the US geostrategy in Asia.

Washington has decided to relocate the USFJ command to Tokyo due to the various shortcomings surrounding its existing relationship with the JSDF forged during the Cold War. Founded in 1957, the USJF succeeded the Far East Command (FECOM) headed by General Douglas MacArthur and other WWII-era generals and has been in Japan for nearly 70 years largely as a forward-deployed logistical force. This is due to Washington’s Cold War-era view of Japan as an unsinkable aircraft carrier serving as the US military’s key logistical hub in Asia. Indeed, Japan emerged as a key logistical base for the US military operations during the Korean War and subsequently proved its newfound value when the US fought in Vietnam and, later, in the Middle East. Therefore, the USFJ defines its mission as follows:

USFJ manages the U.S. — Japan Alliance and sets conditions within Japan to ensure U.S. service components maintain a lethal posture and readiness to support regional operations in steady state, crisis, and contingency and that bilateral mechanisms between the United States and Japan provide the ability to coordinate and synchronize actions in support of the U.S. — Japan Alliance.

The premise behind this mission statement is that the US military power in Asia is so robust that it would not warrant the USFJ’s role in defending Japan. In other words, the defense of Japan is fundamentally the responsibility of the JSDF, and the USFJ is obligated to support the Japanese ally only so long as it is conducive to US military operations in Asia. This was evident in the USFJ’s ancillary logistical role in supporting the JSDF’s military operations other than war (MOOTW) in disaster relief following the 2011 Fukushima nuclear meltdown. As a result, the USFJ’s command continues to remain headquartered in Hawaii, almost 4,000 miles from Japan. Until recently, this Cold War-era burden-sharing arrangement assumed in the USFJ mission had worked perfectly even after Tokyo globalized the JSDF’s operational scope with the passage of the 2015 security legislation. However, the growing threat of China’s anti-access/area-denial (A2/AD) strategy enabled by emerging technologies, such as hypersonic missiles, has exposed the tyranny of distance, challenging the USFJ’s very mission due to Japan’s continued embrace of strategic passivity stemming from its post-WWII pacifism.

The coming US joint command in Tokyo will seek to remedy this emerging problem for the USFJ by upending its existing role and relationship with the JSDF. It would inevitably lead the USFJ to assume a warfighting role in and around Japan, including the defense of Japan. Indeed, Beijing’s growing military modernization would threaten the US military bases in Japan, particularly in Okinawa, forcing the USFJ to de facto assume the defense of Japan as part of its mission. This would be a radical departure from the USFJ’s historical logistics-driven mission, signifying the veritable return of its predecessor, the FECOM, a joint combatant command headquartered in Tokyo between 1947 and 1957. In other words, Japan will once again become the Far Eastern frontline from which to thrust the US military power onto Eurasia just as it was during the Korean War. However, this does not necessarily mean US boots on the ground in future wars in Asia. Indeed, the growing isolationist nationalism under the slogan of America First would threaten US power projection in Asia and even the US-Japan alliance itself. Indeed, the US could theoretically withdraw from the 1960 US-Japan Security Treaty which reached its expiration in 1970 and has been automatically renewing itself unless either or both parties leave. In other words, the creation of the USFJ joint command in Tokyo alone would hardly assure continued US military commitment to Japan.

In fact, the simultaneous launch of the proposed JSDF joint command in Tokyo appears to remedy this problem. The latest US-Japan 2+2 summit revealed that the USFJ and the JSDF would coordinate with each other in running their respective joint commands in Tokyo. In other words, the emerging dual joint command system in Tokyo will be structurally different from the Combined Forces Command (CFC) model in South Korea in which the Republic of Korea (ROK) military is subordinate to the US Forces in Korea (USFK). Yet, such a structural difference would be irrelevant in practice due to the obvious capability gaps between the two allies. For example, the JSDF would inevitably find itself utterly reliant on the USFJ for intelligence, especially signals intelligence (SIGINT) inside Japan due to Article 21 of the 1947 Constitution of Japan guaranteeing the secrecy of correspondence. If Beijing’s unrestricted warfare seeks to foment domestic unrest in Japan, the JSDF would have no choice but to depend on the USFJ for intelligence to deter it. This is one of numerous capability gaps between the US and Japan, and the JSDF would therefore be inevitably subordinate to the USFJ in operational command. Moreover, Japan’s political subordination to the US would almost certainly be mirrored in the putative coordination between the emerging two joint commands in Tokyo. As a result, the USFJ could theoretically dominate the JSDF’s command. This in turn would mean the reversal of the traditional sword-and-shield dynamics characterizing the US-Japan alliance for decades. The creation of the USFJ command would increasingly lead Japan to unsheathe the sword and the US to hold the shield given the inexorable rise of America First isolationist nationalism in domestic US politics.

While the future of the USFJ-JSDF relationship remains to be seen, the rise of the USFJ joint command in Tokyo signifies the triumph of MacArthur over Admiral Chester Nimitz in the evolution of the US geostrategy in Asia. America’s two WWII heros laid the foundation for the US military presence in Japan today. During the Pacific War, both MacArthur and Nimitz supported and implemented the leapfrogging strategy inspired by the War Plan Orange and Marine Corps Lt. Col Earl Hancock Ellis’ prophetic Operations Plan 712: Advanced Base Operations in Micronesia. Yet, while Nimitz adopted a maritime approach focused on denying Imperial Japan’s sea lanes of communication through unrestricted submarine warfare, MacArthur sought to expand America’s land power in the Pacific, leading him to capture large swathes of regional landmass, including the New Guinea and the Philippines, culminating in the Allied occupation of Japan after WWII. Their different approaches to the leapfrogging strategy were evident in their divergent command styles. Apart from their personality difference, whereas Nimitz largely resigned himself to Hawaii and, later, Guam, MacArthur always found himself on the frontline from Bataan all the way to the Tokyo Bay where he personally sealed Imperial Japan’s unconditional surrender aboard USS Missouri. In a sense, MacArthur’s occupation of Japan and his command in the Korean War were merely a continuation of his leapfrogging strategy from the Pacific War. His unceremonious layoff by President Harry Truman in 1951 forced him to return to the US, leading Nimitz to influence the subsequent US geostrategy in Asia. The upshot was the USFJ’s detached command subsumed within the Pacific Command (PACOM) and, later, the INDOPACOM, leading the US-Japan alliance to become a maritime alliance guided by the US Navy (USN) and the Japanese Maritime Self-Defense Force (JMSDF). By contrast, the upcoming launch of the USFJ joint command in Tokyo signifies the return of MacArthur’s land power-driven geostrategy focused on the defense of Japan, South Korea, the Philippines, and other regional US partners, such as Taiwan, against the Eurasian continental powers.

In this sense, the proposed USFJ joint command in Tokyo would also have enormous political implications for the US-Japan alliance. The presence of a US military joint command in Japan’s capital would mean the return of MacArthur’s FECOM or even his General Headquarters, the Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers (GHQ/SCAP) which oversaw the occupation of Japan. Interestingly, the Japanese government requested a four-star US general to head the proposed USFJ joint command in Tokyo as opposed to a three-star officer proposed by Washington. Tokyo’s bizarre request underscored its continued desire to perpetuate its longstanding strategic passivity to induce greater US military involvement, an attitude unchanged since the days of allied occupation under MacArthur. Yet, Tokyo’s deliberate subordination to Washington would most likely turn against itself in the age of America First. In other words, Japan has unwittingly positioned itself as a pawn for the emerging US geostrategy in Asia in which the JSDF would find itself on the frontlines of future regional wars commanded by the USFJ. For the US, this would mean ultimate victory over Japan as it could now de facto command Asia’s foremost military power. For Japan, it could allow Tokyo to implement radical national security reforms, including even constitution revision, by invoking US pressure. While left unanswered would, of course, be the perennial question of Japan’s national will to fight given its lingering pacifism, the latest US-Japan 2+2 summit has achieved a breakthrough in the evolution of the US geostrategy in Asia and Japan’s security normalization.

When MacArthur delivered his famous farewell address to the joint session of Congress in 1951, he prophetically warned against the rise of China in Asia. Drawing attention to the growing territorial ambitions of “Red China” at the time, he called for the bolstering of littoral defense along what would later become known as the First Island Chain, particularly Taiwan. The fall of Taiwan to Beijing “would at once threaten the freedom of the Philippines and the loss of Japan and might well force our western frontier back to the coast of California, Oregon and Washington.” He then turned to Japan and expressed his high hopes for the newly-resurrected country which he guaranteed “will not again fail the universal trust.” In his subtle rebuke to Truman’s consequential decision over MacArhutr’s fate during the Korean War, he concluded his speech by reciting a verse from a popular barrack ballad and uttered, “I now close my military career and just fade away, an old soldier who tried to do his duty as God gave him the light to see that duty.” While the Hero of Corregidor has long faded away into the annals of history, his legacy is increasingly palpable with the advent of the USFJ joint command in Tokyo as if God has given him a second chance in heaven. Indeed, post-WWII Japan is MacArhtur’s great experiment, and the ball is truly in Tokyo’s court whether or not the country can live up to the old American general’s lofty expectations.

Hidetoshi Azuma is a CSPC Senior Fellow.

News You May Have Missed

Burkina Faso on the Brink

Burkina Faso is currently facing a multifaceted crisis, marked by escalating violence from extremist groups, political repression, and a dire humanitarian situation. The country has been plagued by attacks from militant organizations linked to al-Qaeda and the Islamic State, which have exacerbated an already fragile security situation. A recent attack on a military base near Mansila resulted in over 100 soldier casualties, highlighting the military junta’s struggles to maintain control. This insecurity has led to over 2 million people being displaced, with many living in precarious conditions and lacking basic necessities. The government, led by Captain Ibrahim Traore, has cut ties with traditional Western allies such as France, and instead sought military support from Russia, including the controversial Wagner Group, now known as Africa Corps, to bolster its forces.

In the political realm, Traore’s junta has increasingly relied on repressive measures to maintain power. Elections that were initially promised have been postponed for five years, effectively extending military rule indefinitely. Political parties have been banned, and opposition leaders, journalists, and activists have faced arrests and disappearances. Reports of human rights abuses by security forces against civilians accused of collaborating with insurgents have also increased, further deepening the humanitarian crisis.

In an attempt to consolidate power, the junta has fostered closer ties with Russia, leading to a rise in anti-Western rhetoric and disinformation campaigns within the country. Despite the turmoil, Traore has sought to project an image of restoration of sovereignty and stability, though the situation remains precarious and the international community continues to express concern over Burkina Faso’s trajectory. Meanwhile, the junta’s decision to withdraw from the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) and form a new alliance with neighboring Mali and Niger, who have experienced recent military coups in 2021 and 2023 respectively, has raised questions about regional stability and cooperation in addressing shared security challenges.

Saakshi Philip is a CSPC Intern.